We found a treasure along the Kwazulu-Natal Coast!

We had looked forward to our first visit to Umlalazi Nature Reserve in March with great excitement, but what we found at this little jewel exceeded our expectations many times over.

Compared to many other South African conservation areas, Umlalazi is tiny. The reserve may cover only a little over 1000ha, but it is the amazing diversity of ecosystems it protects that make it such a valuable piece of land. The estuary of the Mlalazi River is considered among the top 20 most important to conserve of more than 250 South African estuaries. Another watercourse, the Siyayi, runs parallel to the sea for a distance of about 8km through the reserve, though only reaches the ocean after episodes of extreme rainfall as its mouth has been blocked by the dunes at Umlalazi’s main beach. The reserve is well known for the excellent examples of mangrove forests it protects, but you’ll also find swamp forests dominated by Swamp Fig trees (Ficus trichopoda), climax dune forests, Acacia thickets, tidal salt marshes, freshwater wetlands, coastal grasslands, seashore dune vegetation as well as miles of unspoiled beaches. A grove of Kosi Palms (Raphia australis), one of the largest species of palm in the world, was planted in 1903 by a magistrate C.C. Foxon and is today regarded a national monument.

Umlalazi sunset

Umlalazi sunrise

The lazy Mlalazi

A beach that stretches for many miles!

Swamp Forest

Mangroves lining the lagoon at Umlalazi Nature Reserve

Kosi Raphia Palm grove

Dune forest

The reed-grown Siyayi River

Of course, with such a huge diversity of habitats it should come as no surprise that Umlalazi is home to an equally impressive variety of animal life. The abundance of invertebrate species of all descriptions is simply astounding. Thirteen mammal species have been recorded, with plains zebra, red duiker and vervet monkey being the most easily seen. The critically endangered Pickersgill’s Reed Frog is among 15 species of amphibians found in the reserve, while nile crocodile, python and gaboon adder feature in the list of 16 reptile species – 9 of which snakes – you might encounter. With a list of 327 bird species identified, the reserve is a prime destination for birdwatchers – pride of place of course going to the southern most breeding population of Palmnut Vultures that feed and nest in the Kosi Palms. These small vultures (wingspan of 1.5m, weight up to 1.8kg) is one of South Africa’s rarest birds, but regularly encountered here at Umlalazi, and apart from the fruit of the palms will also feed on carrion and small animals.

Mantid

Red Duiker

Red Duiker and Vervet Monkeys at home in Umlalazi

Woolly-necked stork taking flight

Vervet monkeys raid picnic sites next to the river

Vervet Monkey

White-eared Barbet

Giant land snail

Brown-hooded Kingfisher

Striped Skink

Vervet Monkey

Vervet Monkey in a mangrove tree

Palm-Nut Vulture, Umlalazi Nature Reserve, March 2016

Pill-millipede

These three zebras seemed to act as our hosts while we were visiting Umlalazi and regularly passed by. They even formed a guard of honour at the gate when we departed 😀

The three horses of Umlalazi

The three horses of Umlalazi

The three horses of Umlalazi

The three horses of Umlalazi

The three horses of Umlalazi

The three horses of Umlalazi

In upcoming posts, we’ll focus some more attention on Umlalazi’s mangroves, the estuary, the forests and the beach.

The focus for Umlalazi’s human visitors is on outdoor recreation, with fishing, boating, canoeing (can be hired at reception), hiking, birding, swimming, surfing and picnicking being popular pursuits. Excellent information displays at the trail heads and other public areas give visitors an insight into the world they are exploring.

Picnic site on the banks of the Mlalazi

Beware the crocodiles!

Excellent information boards explain the different habitats

Excellent information boards explain the different habitats

Excellent information boards explain the different habitats

Excellent information boards explain the different habitats

Excellent information boards explain the different habitats

Hiking through the forest

Watersports are popular with Umlalazi’s visitors

The reserve is managed by Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, through whom overnight visitors can also book the twelve fully self-contained 4-sleeper log cabins, the 14 camping sites at Indaba Camp or the 36 camping sites at Inkwazi Camp available inside the reserve. The town of Mtunzini, just outside the reserve gates, also offers several alternative accommodation options, as well as a variety of other services you’d expect in a small holiday town. The area’s modern history dates back to the 1850’s when the colourful character John Robert Dunn settled here. Dunn befriended Zulu King Cetshwayo who appointed him Chieftain over the area that Umlalazi and Mtunzini lies in today. He held his court and celebrations under a large red milkwood tree (known as the Indaba Tree) in what is now the Indaba campsite at Umlalazi. Dunn died in 1895, having married 49 wives (48 of which according to traditional Zulu custom) and fathering over a hundred children (various sources give differing numbers about exactly how many – ranging from 116 to 163!). That same year, a magistrate was appointed at Mtunzini, marking the official birth of the town. Umlalazi Nature Reserve itself was proclaimed in 1948 and today forms the northernmost section of the Siyaya Coastal Park which stretches for 37km along the coastline and also incorporates the Redhill and Amatigulu Nature Reserves.

Umlalazi Log Cabin, March 2016

Indaba Campsite

Plaque commemorating John Dunn at Indaba Campsite

Indaba Campsite

Indaba Campsite

Inkwazi Campsite

Inkwazi Campsite

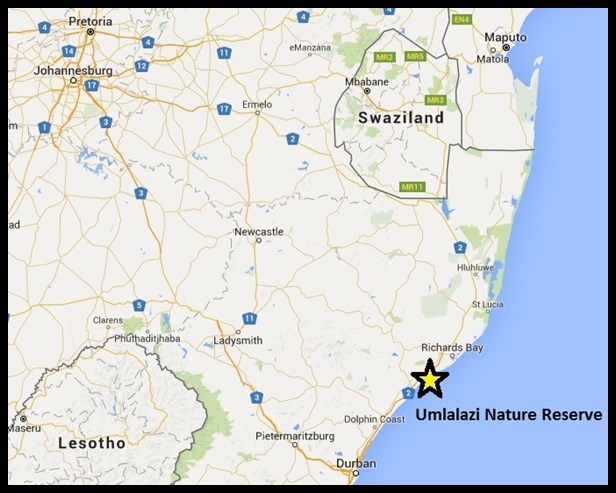

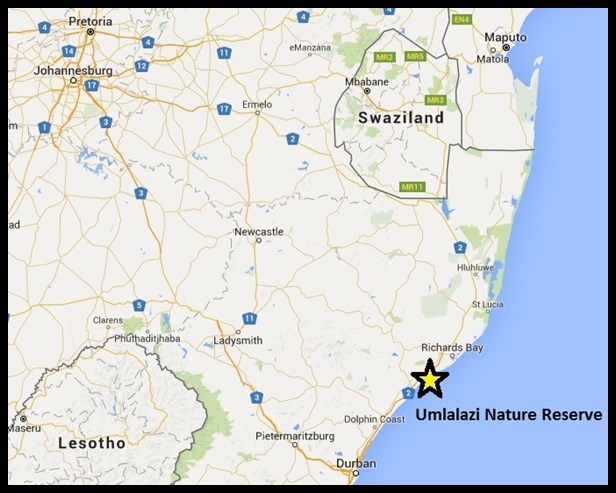

Umlalazi Nature Reserve is located on the Indian Ocean, along Kwazulu-Natal’s North Coast about 140km from Durban (or 700km from Pretoria), and easily accessed from the Mtunzini off-ramp from the N2-highway.

How to reach Umlalazi