First, a bit of history about the iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Lake Saint Lucia is Africa’s largest estuarine system. When fully inundated the lake is approximately 65km long and 21km across at its widest point and covers approximately 360km² (Google Earth view here). On average the lake is around 1m deep, reaching up to 3m deep in places. It is fed by several major rivers, including the Mfolozi, Mkuze and Hluhluwe, and dozens of minor streams, and seepage from the high dunes separating the lake from the Indian Ocean. This intricate system maintains a treasure trove of habitats and biodiversity.

In 1822 the British Navy surveyed this coastline with three ships, with a Lieutenant Vidal (see Cape Vidal below) being the master of one of them. In the ensuing years big game were decimated by white hunters and explorers and in less than a hundred years most of the wildlife of the area were entirely eradicated from the lake shore. Elephants and hippos were especially targeted for export of their ivory tusks.

From the 1880’s Christian mission stations were established at Cape Vidal, Ozabeni and Mount Tabor (the latter being close to present-day Mission Rocks). These operated until the 1950’s when the government forced the local population to move.

Britain annexed the area around the estuary of Lake St Lucia in December 1884 and St Lucia town was proclaimed only a year later, becoming a popular resort already by the 1920s when the first hotel opened. Until the 1950s, when a bridge was built across the St Lucia estuary, the town was connected to the outside world by a pont.

St Lucia Game Reserve, 368km² in extent and comprising the lake and its islands, was proclaimed a protected area in April 1895 when it was realised that the local populations of almost all big game species had been virtually wiped out.

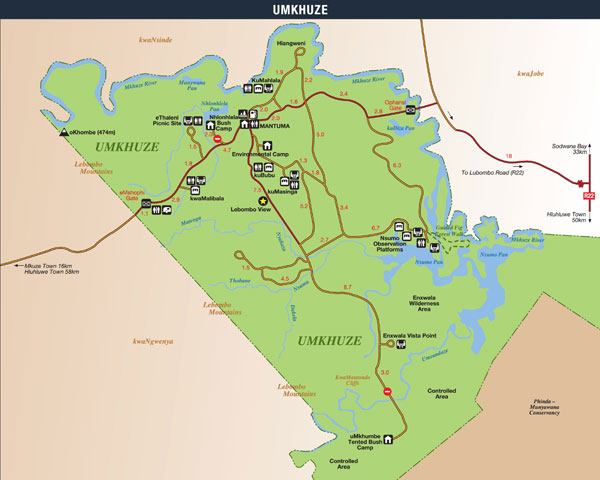

The Mkuze Game Reserve was gazetted in 1912 (originally 251km² in extent and later enlarged to 400km²). (Note: We’ll delve into uMkhuze’s history a little more in our next installment).

From 1911 the Umfolozi flats were planted with sugar cane, leading to the mouth of Lake St Lucia silting up by the early 1950’s. To alleviate this, the Mfolozi River’s mouth was manually diverted away from the lake, cutting off 60% of the vital freshwater supply for the estuarine system and requiring the St Lucia mouth to be dredged continuously to keep it open. This situation was reversed between 2012 and 2016 when the Mfolozi River was again rerouted to empty into the lake. Flow in the river however is now substantially depleted by users upstream and the lake’s mouth remains closed except during periods of exceptional rainfall. This in turn is leading to conflict with the sugar cane farmers who feel their livelihoods threatened by the lake backing up into the Mfolozi River and flooding their fields.

In 1939 a half-mile (800m) wide strip surrounding most of the lake was proclaimed as St Lucia Park, which includes the popular fishing destinations of Charter’s Creek and Fanie’s Island.

In 1943, at the height of the 2nd World War which saw 163 ships sunk around the South African coast, the Royal Air Force established a base for Catalina Flying Boats at Lake St Lucia to patrol for enemy submarines. The base was abandoned in 1945 after hostilities ended, but the area is still known as Catalina Bay. From the viewing deck erected here by the Park authorities visitors have a wonderful view over the waters of Lake St Lucia.

A section of the lake shore in the False Bay area was declared the False Bay Park (22km²) in 1944.

Sodwana Bay (4km²) was proclaimed a national park, under the auspices of the Natal Parks Board, in December 1950.

The Kosi Bay Nature Reserve, later 110km² in extent, was proclaimed in January 1951.

Still, it seemed that authorities could not fully commit to the protection of Lake Saint Lucia and its environs, and exotic pine plantations were established on the western and eastern shores of the Lake from 1952 in designated “State Forests”. These thirsty exotics used up most if not all of the freshwater seepage from the surrounding dunes and marshes, further drying up the lake and pushing up its salinity.

Further sacrilege ensued in 1968, when the wilderness area of the lake was sacrificed for a missile testing range that operated until 1990.

In 1975, fortunes for Lake Saint Lucia finally started turning again. The South African government was one of the first signatories to the Ramsar Convention, and the Greater St. Lucia Wetland region was one of the first sites designated under the treaty.

The St Lucia Marine Reserve, extending 5km from the coast into the Indian Ocean along the stretch of coats between Cape Vidal and Sodwana, was declared in 1979.

Until 1969, Nile crocodiles were classed as vermin in the Natal province, and their numbers were severely depleted by hunters killing them for their skins and because of the danger they posed to people and livestock. By the time their vital ecological significance was realised in the mid-60’s the local population was almost completely wiped out, and the Natal Parks Board took steps to breed and release crocodiles into conservation areas where they were exterminated. So successful have these efforts been that Lake St Lucia alone today has a population of about 1,200 adult crocodiles. The St Lucia Crocodile Centre opened in 1979 at a site just 3km north of the town, at the Bhangazi Gate into the Eastern Shores section.

In early 1984, in the wake of devastating Cyclone Demoina, abnormally high runoff from the rivers feeding into the lake scoured clean the estuary mouth. This had a positive impact on the health of the lake system until about 1993, when a drought caused the mouth to close again, requiring the use of heavy machinery to keep it open.

The Maputaland Marine Reserve was established in 1986 to protect the stretch of coastline from Sodwana to Kosi Bay.

The Eastern Shores State Forest (now known as Mfabeni), Cape Vidal State Forest (now known as the Tewate Wilderness Area) and Sodwana State Forest (now known as Ozabeni) were transferred to the control of the Natal Parks Board (now Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife) in 1987, allowing the provincial conservation agency to commence with the reintroduction of game indigenous to the area.

In February 1990, national government signaled its intentions to establish the Greater St Lucia Wetland Park, which would be the third biggest conservation area in the country following the amalgamation of all the separate proclaimed conservation areas around the lake. A mining company, Richards Bay Minerals, however had plans to mine the ecologically sensitive forested dunes on the Eastern Shores for titanium. This resulted in one of the most comprehensive environmental impact studies ever undertaken in South Africa, and in December 1993, in the face of enormous public pressure, the panel reviewing the study recommended unanimously in favour of the area being declared a national park, eligible for World Heritage Status.

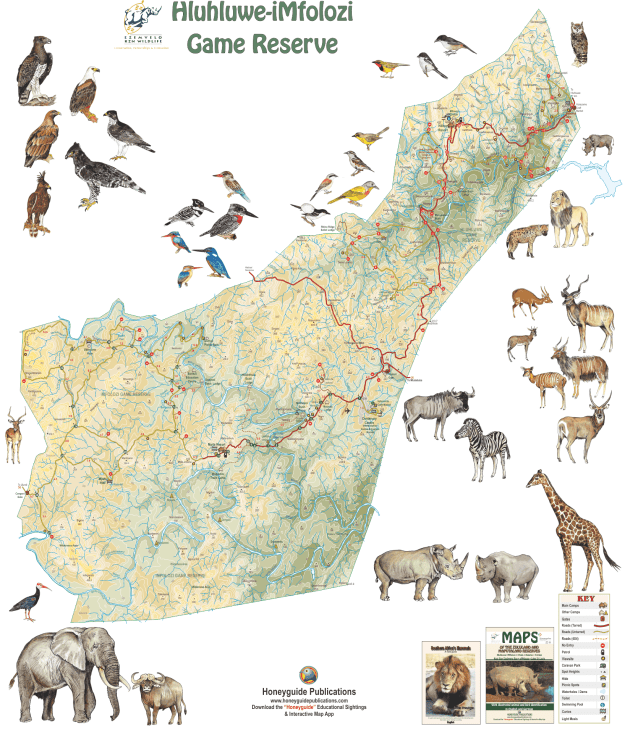

The proposed Greater St Lucia Wetland Park would incorporate the Cape Vidal State Forest, Dukuduku Forest, Eastern Shores State Forest, False Bay Park, Kosi Bay Nature Reserve, Makasa Nature Reserve, Mapelane Nature Reserve, Maputaland Marine Reserve (including Lake Sibaya, Mabibi, Lala Neck and Black Rock, Rocktail Bay), Mkuzi Game Reserve, Nyalazi State Forest, Sodwana Bay National Park, St Lucia Game Reserve, St Lucia Marine Reserve and St Lucia Park.

At the time the proclamation of the Park was promulgated it was decided that the exotic pine plantations that covered extensive parts of the envisaged Park would not be replaced when they were harvested, a process that would still take many years to accomplish. Today it is wonderful to see nature claiming back these ravaged areas after the exotic trees are felled, aided in no small way by fruit-eating birds and bats distributing the seeds of indigenous forest trees throughout these parts.

The Greater St. Lucia Wetland Park was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in December 1999 in recognition of its “unique ecological processes, superlative natural phenomena and exceptionally rich biodiversity”, to quote three of the ten criteria UNESCO considers when including sites in this prestigious club. In 2007 the name of the Park was changed to the iSimangaliso Wetland Park, the isiZulu word meaning “miracle” or “wonder”.

Today, the Park protects 230km of the Indian Ocean coastline and adjacent interior as well as a marine reserve, stretching from Kosi Bay on the border with Mozambique to Maphelane in the south, covering a total of 13,289km² of marine and terrestrial habitats (the marine component covers 10,700km² of the Indian Ocean). Within its borders the Park accommodates at least 115 mammal species, 526 kinds of birds, 100 reptiles, 48 amphibians, about 90 freshwater fish species and more than 1,200 kinds of marine fish (including the coelecanth), and 282 kinds of butterflies!

The Park and surrounds attract around 2-million visitors annually and tourism and associated services is a major source of employment in an otherwise severely impoverished corner of the country.

The Eastern Shores, including Mission Rocks and Cape Vidal

By the time the Portuguese seafarers “discovered” the mouth of Africa’s biggest estuarine system and named it Santa Lucia in 1575, the area had been settled by Nguni pastoralists for several hundred years already. They were responsible for establishing and maintaining much of the grasslands on the Eastern Shores, which in turn supported many species of animals.

Sunrise on the Eastern Shores, iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Sunrise on the Eastern Shores

Sunrise on the Eastern Shores

Sunrise on the Eastern Shores

Sunrise on the Eastern Shores

Sunset on the Eastern Shores

Sunset on the Eastern Shores

The Eastern Shores of Lake Saint Lucia is among the most diverse ecosystems in the country. Here, rocky intertidal pools and sandy beaches are bordered by some of the highest vegetated dunes in the world, densely covered by forests of tall tropical trees and luxuriant undergrowth. Where the dune forests end, grasslands and marshes, punctuated by dispersed trees, clumps of palms and seasonally inundated pans take over. Stands of swamp forests line small water courses and, on the shores of Lake St Lucia, dense beds of reeds and papyrus are interspersed with stands of mangrove trees. Rainfall averages as high as 1200mm annually of which two thirds fall in the spring and summer months.

Sunrise over the Eastern Shores

Sunrise over the Eastern Shores

Kudu bull standing proudly on the crest of a grassy dune

Mziki viewsite

The Red Dunes at eSibomvini

Buffaloes at sunset

Herd of buffalo on the Mfabeni swamp

Mfabeni landscape

Amazibu Pan

Rainbow along the Grassland Loop

Spotted Hyena

Thick fog blanket the Mfabeni swamp

Ghost Crabs on the beach at Cape Vidal

Cape Vidal

Rock pools at Cape Vidal

Lake St Lucia and surrounds has a large population of Nile crocodiles, probably the most significant population in the entire country.

Swimming crocodile

Swimming crocodile

Crocodile on shore

Nile Crocodile at the mouth of Lake St. Lucia

Crocodile

Hippos survived the onslaught of the 19th and 20th centuries, and today there are about 1,000 in the lake and surrounding pans and wetlands. They’re also regularly seen on the Eastern Shores. Hippos are considered ecosystem-engineers, playing a vital role in cycling nutrients back to the wetlands and opening channels through marshes, preventing them from clogging up and stagnating.

Hippo close-up

Curious hippos

Hippo

Pod of hipos

Hippopotamus

Hippopotamus

Hippo

The last elephant in the region of Lake St Lucia was killed in the Dukuduku Forest on the western shores in 1915. Twenty-four elephants were reintroduced to the Eastern Shores in 2001, and today the population of elephants around Lake St Lucia has grown to over 100. The current elephant population follow the same ancient migratory paths across the lake that elephants used for millennia before they were wiped out from the area.

Elephant

Elephant

Elephant bull emerging from the forest (photo by Joubert)

Young elephant showing off (photo by Joubert)

Elephant drinking from a seasonal pan

Young elephant having a good scratch

Elephant herd on a stroll (photo by Joubert)

Young elephant showing off (photo by Joubert)

Elephant roadblock between Cape Vidal and St. Lucia

Elephant roadblock between Cape Vidal and St. Luciack (photo by Joubert)

Elephant cow keeping the youngsters safe

Dancing elephant (photo by Joubert)

Elephant procession passing the turnoff to Mission Rocks (photo by Marilize)

Elephant cow emerging from the forest to find us in her way (don’t worry, we moved away quickly!)(photo by Joubert)

Elephant herd blocking the road…again!

Most of the white rhinos on the Eastern Shores have been dehorned to deter poachers.

Lazy White Rhinos

White Rhinos

White Rhino

White Rhinos

The Eastern Shores is a stronghold of the black rhino, but owing to their solitary and nocturnal natures they’re not seen often.

Black Rhino on the eastern shores of Lake St. Lucia

Buffaloes are one of the most commonly seen large animals on the Eastern Shores.

Young buffalo bull

Buffalo bull

Buffalo

What a buffalo looks like just before he charges!

Buffalo

Buffalo

Buffalo road block

Herd of buffaloes

Buffalo bull

Buffalo bull (photo by Joubert)

Buffalo in the golden glow of sunset

Wary Buffalo bull

Buffalo bull

Buffaloes

Buffalo bull

The Eastern Shores has a healthy leopard population and these beautiful cats are seen fairly regularly.

Leopard sighting on the Grassland Loop on the Eastern Shores of Lake St Lucia – 15th June 2015

Leopard on the prowl

Leopard in golden early morning sunshine

Leopard in golden early morning sunshine

Leopard hiding in long grass

Leopard on the edge of the forest during a rainy spell

The population of spotted hyena on the Eastern Shores seems to be growing, as sightings have become much more frequent in recent years.

Leader of the clan

Scruffy-looking Spotted Hyena

Spotted Hyena (photo by Joubert)

Spotted Hyena

Spotted Hyena cub near Cape Vidal

Spotted Hyena

Four of South Africa’s five primate species occur on the Eastern Shores. It holds one of the country’s largest populations of the rare samango monkey, in addition to baboons, vervet monkeys and thick-tailed bushbabies.

Baboon in repose

Baboon

Chacma Baboon

Samango Monkey

Samango Monkey

Male Samango Monkey

Samango Monkey

Samango Monkey

Samango Monkey

Samango Monkey

Samango Monkey

Samango Monkey

This leucistic Samango Monkey is a familiar inhabitant of Cape Vidal

Vervet Monkey

Alarmed Vervet Monkey

Vervet Monkey

Baby Vervet Monkey

Vervet Monkey

Cute little Vervet Monkeys – just look at that smile!

Thick-tailed Bushbaby

Thick-tailed Bushbaby

Almost all the other herbivores that once roamed the area are now represented once more.

Tsessebe

Kudu bull

Plains zebra

Kudu family

Blue Wildebeest

Bushbuck

Reedbuck

Waterbuck

Red Duiker

Waterbuck bull

Bushpig boar

Bushpig sow

Sleepy Warthog

Enormous Kudu bull in the Mfabeni Swamp

Kudu bull

Bushbuck ram

Kudu calf nursing

Red duiker

Red duiker

Red Duiker

Impala

Impala ewe

There’s an extraordinary variety of bird life on the Eastern Shores, and especially forest and water-dependent birds are well represented.

Crested Guineafowl family

Spur-winged Goose

Steppe Buzzard

Fan-tailed Widowbird

Secretarybird

Livingstone’s Turaco

African Green Pigeon

Crested Guineafowl

Red-capped Robin Chat

Crowned Eagle

African Pygmy Kingfisher

Cinnamon-breasted Bunting

Collared Sunbird

Blue-cheeked Bee-eaters

Black-bellied Starling

Crowned Hornbill

Yellow-throated Longclaw

Red-breasted Swallow

Blue-cheeked Bee-eater

Grey-headed Gull

African Marsh Harrier

Saddle-billed Stork in silhouette at sunrise

Hadeda in flight – photo by Joubert

Denham’s bustard

Yellow-throated Longclaw

Crested Guineafowl – iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Southern Banded Snake Eagle

Pink-backed Pelicans – iSimangaliso Wetland Park

White-eared Barbets – iSimangaliso Wetland Park

African Olive Pigeon

Baillon’s Crake

Dark-backed Weaver

Square-tailed Nightjar

Woolly-necked Stork

Yellow-fronted Canary

Brown Snake Eagle

Green-backed Camaroptera

Martial Eagle

Caspian Tern

Yellow Weaver

Aside from crocodiles, the tropical environment of the Eastern Shores sustains an impressive variety of reptiles and amphibians. It is a crucial nesting place for endangered leatherback and loggerhead sea turtles.

Tropical House Gecko

Bell’s Hinged Tortoise

Tiny little Bush Squeaker frog

Eastern Coastal Skink

Water Monitor lizard

Eastern Coastal Skink

Bell’s Hinged Tortoise

Giant Legless Skink

Common Tropical House Gecko

Eastern Coastal Skink

Variegated slug eater

This juvenile Painted Reed Frog climbed into my coffee cup at Mziki viewpoint one morning – at which stage during the drinking process I don’t know…

The diversity of insects – particularly butterflies – and other invertebrates that thrive on the Eastern Shores is simply astounding.

Tailor Ants nest

Pill-millipede in defensive posture

Giant African Land Snail

Natal Acraea butterfly

Praying Mantis at Catalina Bay

Scorpion (Uroplectus formosus) found at Cape Vidal

Interesting caterpillar

Natal Acraea

Citrus Swallowtail

Streaked Sailer

Spotted Hairtail

Wasp with Sac Spider prey

Elegant Grasshopper

Cicada

Unidentified Dragonfly (photo by Joubert)

Unidentified caterpillar, probably of a moth species

Boisduval’s Tree Nymph (female)

Female Mocker Swallowtail mimicking the Friar butterfly

African Migrant

False Dotted Border

Jaunty Dropwing Dragonfly (female)

Common Bush Browns in flight

Unidentified Flightless Wasp

Variable Diadem

Wasp of the genus Stizus

Carpenter Bee Robber Fly

Sundowner Moth

Small Orange Tip

Green-banded Swallowtail butterflies

Novice butterflies

Dung Beetle with his bounty

Adult Antlion

Novice (Amauris ochlea)

The multitude of species to be seen on the beaches and in the rock pools along the Indian Ocean coastline is equally impressive, and there are even huge marine mammals to be seen just offshore!

Littoral life at Cape Vidal

Littoral life at Cape Vidal

Daredevil Surfing Ghost Crab

Natal Rock Crab

Little Blenny fish in a rock pool at Mission Rocks

Crab at Mission Rocks

Convict Surgeonfish in a rock pool at Cape Vidal

Hermit Crab – iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Humpback Whale

Humpback Whale

Dolphins in the waves at Cape Vidal

Dolphins in the waves at Cape Vidal

The small holiday town of St Lucia is the gateway to the lake’s estuary and the Eastern Shores section of the iSimangaliso Wetland Park. The town offers all the amenities you’d expect from a holiday destination, with shops and restaurants, doctors and dentists, a police station, and several accommodation and camping options. There are outdoor market stalls where the locals sell curios and fresh produce. The beach just outside town is excellent for fishing and swimming and general beach activities. Guided boat tours are available on the estuary and deep sea fishing excursions can be arranged. Guided drives, horse rides, and walks on the Eastern Shores are offered from St Lucia and in season whale watching trips and night-time visits to turtle-nesting sites are very popular. A forested portion of the town is traversed by the Gwalagwala Trail.

Sign in St Lucia town warning about the presence of hippos

Holiday accommodation in Saint Lucia town

Manzini Chalets #9, St. Lucia Town, July 2017

Lake St Lucia estuary

Santa Lucia

Santa Lucia

Getting up close to a crocodile

Hungry hungry hippo!

Crocodiles on a sandbank near the mouth of the lake

Gwalagwala Trail

Gwalagwala Trail

Mouth of Lake Saint Lucia, here closed off from the sea

St. Lucia mouth

The mouth of Lake St. Lucia, with the Umfolozi River coming in from the front and the lake from the right, with the ocean to the left of the image

Where Lake St. Lucia meets the Indian Ocean

At the St Lucia Crocodile Centre, in addition to tours and informative talks at certain times, there is also a well stocked curio shop and tea garden. On display at the centre is Nile crocodiles, alligators, dwarf and slender-snouted crocodiles from central and west Africa, cycads, snakes, tortoises & terrapins. Adjacent to the centre is the St Lucia Game Park where several hiking and cycling trails have been laid out and can be enjoyed at no cost.

St Lucia Crocodile Centre

Entrance to the Crocodile Centre

Educational displays at the Crocodile Centre

Downhill at the St. Lucia Crocodile Centre

Better heed the signs!

Better heed the signs!

Dwarf Crocodile

Slender-snouted Crocodile

Gaboon adder (captive)

Nile crocodile

Nile Crocodile

Nile Crocodile (photo by Joubert)

St. Lucia Crocodile Centre

American Alligator

Cycad garden

Curio shop

Cape Vidal is named after Alexander Thomas Emeric Vidal, master of one of a fleet of three British surveying ships that mapped this coastline in 1822. Anglers “discovered” Cape Vidal in the 1940’s and it quickly became a popular destination for those in the know. Eventually, several private individuals and clubs had built shacks and cabins at Cape Vidal, which was only taken down after the Natal Parks Board were given control of the area and developed the present day camp and day visitor facilities. Today, this pristine area is one of the most popular destinations in the iSimangaliso Wetland Park and an excellent base from which to explore the Eastern Shores of Lake Saint Lucia. The accommodation and campsite is managed by Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife and often booked out months in advance. There’s a fuel station and a small shop selling only basic goods, so it is best to stock-up on your groceries at St Lucia town before entering through Bhangazi Gate 35km to the south of Cape Vidal. Apart from all the activities that the beach caters for, Cape Vidal is also one of the best spots in the country to easily see a wide variety of otherwise very shy forest birds and animals (like Samango Monkeys and Red Duiker).

Cabin 18 at Cape Vidal, iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Cape Vidal Chalet 9, iSimangaliso Wetland Park, July 2017

Log Cabin in Cape Vidal

Log Cabin #1 at Cape Vidal

Log cabin in Cape Vidal

Log cabin at Cape Vidal

Log Cabin 25, Cape Vidal, iSimangaliso Wetland Park, March 2022

Crossing the dune between the camp and the beach at Cape Vidal

The beach at Cape Vidal

Cape Vidal beach

The beach at Cape Vidal

Camping at Cape Vidal

Camping at Cape Vidal

Sunrise at Cape Vidal

Located not far from Cape Vidal, the Bhangazi Bush Lodge, which sleeps 8, is a secluded, exclusive accommodation option on the banks of the lake by the same name.

Lake Bhangazi

Lake Bhangazi

Sunrise over Lake Bhangazi and the forested dunes of Cape Vidal

View over the Eastern Shores and Lake Bhangazi

Named for the mission station that operated at nearby Mount Tabor from 1898 to the 1950’s, Mission Rocks is a scenic spot along the Indian Ocean coast, popular with rock-and-surf fishermen and people who enjoy looking for marine life in rock pools during low tide (like us!). Just a few hundred metres north of the rocks is a pristine beach and further still a series of caves are inhabited by a colony of Egyptian fruit bats. There is a beautiful picnic spot in the forest at the Mission Rocks parking area.

Mission Rocks – iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Mission Rocks

Sunrise at Mission Rocks

Mission Rocks

Mission Rocks – iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Mission Rocks – iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Mission Rocks – iSimangaliso Wetland Park

Mission Rocks

Heart-shaped rock pool at Mission Rocks

Barred Flagtail in a rock pool at Mission Rocks

Mission Rocks picnic spot

On the way to Mission Rocks, visitors should take the time to hike up to the uMziki viewpoint for amazing views of the Indian Ocean and Lake Saint Lucia.

uMziki viewpoint over Indian Ocean

uMziki viewpoint over Lake Saint Lucia

uMziki viewpoint

Mziki viewsite

Lower viewpoint at Mziki

Over the years the road network between Bhangazi Gate and Cape Vidal have been considerably upgraded and expanded, and today visitors have access to around 70km of good tar and gravel roads along which to explore this magical section of the Park.

Scenery along the Vlei Loop on the Eastern Shores of Lake St. Lucia

Vlei Loop

A section of the Grassland Loop cuts through the swamp forest

The road to Cape Vidal

From the viewing deck at Catalina Bay visitors have a wonderful view over the waters of Lake St Lucia.

Catalina Bay lookout

Catalina Bay viewing platform

Rays of sunshine through the clouds over Catalina Bay, Lake St. Lucia

Catalina Bay, Lake St. Lucia

Catalina Bay during the drought

Sunset over Catalina Bay

Sunset over Lake St. Lucia

More spectacular views are on offer from the Kwasheleni Tower along the Dune Loop. The tower was converted from an old fire-lookout tower harking back to the days when the Eastern Shores were used for commercial forestry.

Kwasheleni Tower

Kwasheleni Tower

Steps leading up to the Kwasheleni Tower

Kwasheleni Tower

View towards the north-west from Kwasheleni Tower

Kwasheleni Tower and view

Indian Ocean from Kwasheleni Tower

The view southwards from the Kwasheleni Tower

View southwards from Kwasheleni Tower

View to the south-west from Kwasheleni Tower, with Lake St. Lucia in the background

At the kuMfazana Pan a multi-tiered hide has been built, where photographers can take aim at the profusion of forest and wetland creatures that visit the waterhole.

We dubbed this stretch of the walkway to the hide at kuMfazana “Butterfly Glen”

kuMfazana Hide

KuMfazana Hide

The hide at kuMfazana

kuMfazana Pan

Hippos at kuMfazana Pan

The iSimangaliso Wetland Park is in a part of the country where malaria and bilharzia is endemic, and precautions are advised.