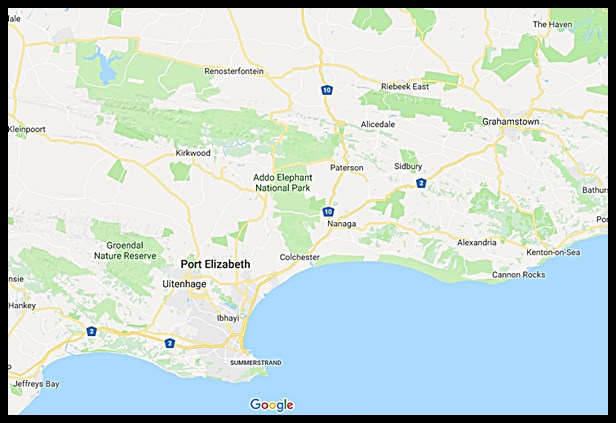

Today we celebrate the 90th birthday of the Addo Elephant National Park.

Scenic road snaking through Addo Elephant National Park

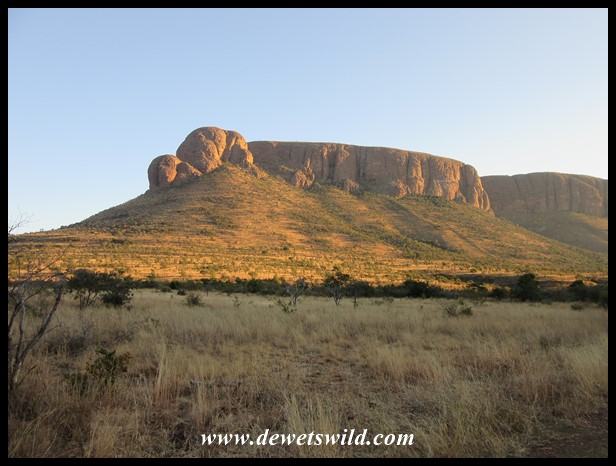

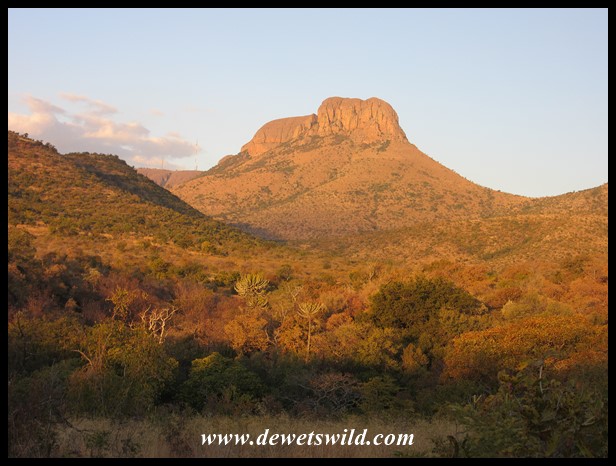

Early morning Addo scenery

Domkrag Dam

Addo Elephant National Park scenery

Addo scenery

View from Addo’s new Nyathi Camp

Addo from the air

By the early 1900’s the Eastern Cape’s wildlife was being exterminated at an alarming rate. The last remaining lions and black rhinos in the region did not see the arrival of the year 1900, and only about 140 African Elephants remained around the Addo district, which was rapidly developing into an important agricultural area, leading to conflict with the newly established farmers. The government’s decision to intervene was not good news for the elephants. In 1919 they appointed Major P.J. Pretorius to destroy the elephants, and by 1920 he had killed 114 of them and caught 2 for a circus. Only 16 elephants remained when public sentiment swung in their favour and the wanton killing ended, and when the Addo Elephant National Park was proclaimed on 3 July 1931, only 11 elephants were left. Initially, the Park was not fenced to keep the elephants in and when they left the Park they were at the mercy of the “civilisation” that wanted to destroy them all, so the first Park manager made the decision to feed them with citrus and other fresh produce to keep them within his boundaries. Slowly but surely their numbers started growing, but by the time the Park, then only 2,270 hectares in size, was finally surrounded with an elephant-proof fence in 1954, there was still only 22 elephants at Addo. The unnatural practice of feeding the elephants, which in the end was done more for the entertainment of tourists than for the elephants’ sake, ended in 1979. By then the herd numbered about 100 animals, but Addo’s elephants have responded wonderfully to the protection they’ve been afforded since the Park’s proclamation, and today number over 600! Along with the elephants, the last free-roaming herds of African (Cape) Buffalo that occurred in the then Cape Province, as well as the unique and endemic Addo Flightless Dung Beetle, finally found a secure refuge. In subsequent years the Park’s area was expanded and species that fell into local extinction were reintroduced.

Herd of elephants making their way to the waterhole

Darn, just missed! (photo by Joubert)

Rowdy elephant youngsters

Baby Elephant tantrum!

Marveling at the skill of an elephant uprooting plants to feed on

Addo Elephants

Addo Elephants

Tiny calf staying close to mom at Spekboom

With the Addo elephants now finally living in a safe refuge, the focus at Addo Elephant National Park is no longer on saving a single species. Today, the park’s management is concerned with the protection of the enormous diversity of landscapes, flora and fauna encompassed within its boundaries, which covers an expansive area of over 178,000 hectares stretching from beyond and across the Zuurberg range to the coastal forests and dune fields of Alexandria. The Park protects portions of no less than five of South Africa’s seven distinct terrestrial biomes, these being subtropical thicket, fynbos, forest, grassland and Nama-Karoo, not to forget to mention the portion of marine environment protected around Algoa Bay’s St. Croix and Bird islands which is important breeding sites for endangered seabirds. Addo is the only National Park in South Africa that can claim to protect the “Big Seven” – the famed “Big Five“ of Elephant, Lion, Black Rhino, Buffalo, Leopard, together with the Great White Shark, and Southern Right Whale.

Addo Elephant National Park protects a total of 95 mammals species. The Park also boasts a list of 417 bird species, and if that isn’t enough, visitors also have a chance of spotting any of the more than 50 reptile species or 20 kinds of frogs and toads that call Addo Elephant National Park home. The Park’s most famous invertebrate inhabitant undoubtedly is the Addo Flightless Dung Beetle (Circellium bacchus), this being only one of 5 places they are still found. These interesting insects make use of elephant and buffalo dung as food, either for themselves or rolled into brood balls in which they lay a single egg before burying it in soft sand and on which the larvae then feeds when it hatches.

Terrestrial Brownbul

Meerkat sentry

Warthog piglet

Red Hartebeest

Cape Robin-Chat

Time to fight about who gets the lion’s share (photo by Joubert)

Kudu on the run

Malachite Sunbird

Black-headed Heron

Pig’s Ear flower

Plumbago flowers

Southern Boubou

Sombre Greenbul at Jack’s Picnic Spot

Addo Flightless Dung Beetle

Buffaloes

Plains Zebra trying to trip an opponent

Kings of Addo, seen near Addo’s new Nyathi Camp

The Addo Main Camp is the Addo Elephant National Park’s first and biggest tourist facility. Camping and a wide variety of accommodation (as well as a swimming pool) is available to overnight guests. There are picnic sites for day visitors, an underground hide overlooking a waterhole frequented by all the Park’s animals and floodlit at night (we even saw a brown hyena there when we visited in December), a birdwatching hide overlooking a small artificial wetland, a self-guided discovery trail, guided drives and horse rides, a fuel station, restaurant, shop and excellent interpretive centre where young and old can learn more about the Park and its inhabitants. Elsewhere in the Park guests can overnight at the luxury, full service and privately-run Gorah, Riverbend and Kuzuko-lodges, or in one of the Park’s own camps at Nyathi, Matyholweni, Kabouga Cottage, Mvubu Campsite, Narina Bushcamp, Langebos and Msintsi. Between the Main Camp and Matyholweni guests have access to an extensive and well-maintained network of all-weather game viewing roads, while other areas of the Park can be explored along hiking trails or 4×4 trails.

Accommodation at Addo with a terrific view of the floodlit waterhole

Family Chalet 16 at Addo Main Rest Camp

Camping at Addo Elephant National Park, December 2017

Addo’s new Nyathi Camp

Addo’s new Nyathi Camp

The easiest way to reach the Park is along the N2 highway from Gqeberha (formerly Port Elizabeth), turning off to the gate at Matyholweni just before you reach the small town of Colchester on the bank of the Sundays River, about 45km from PE’s airport.